Rüdiger Rossig | Journalist | Novinar

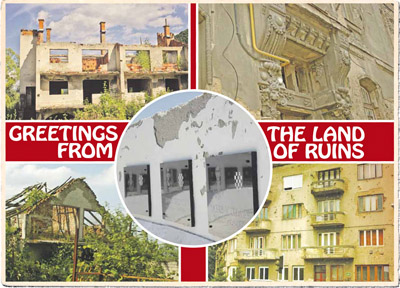

Greetings from the land of ruins

Fotos: Eduarda Cruz (3), Rüdiger Rossig (2)

Fourteen years after the end of the Balkan wars, former Yugoslavia is still a poster child for anti-war tourism | By Ruediger Rossig

German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle (FDP) made a three-day trip to the Balkans in late August. The European region is struggling with the political and physical legacy of conflict.

Along the Adriatic Sea, Croatia is wearing its Sunday best. The sun shines brightly, the water is a deep azure blue, and the towns and villages along the coastal road are picturesque. The majestic Dinaric Alps rise above the sea. This beautiful interplay between nature and culture captivates visitors to the EU candidate country.

The former war zone hits you suddenly after you turn off the coastal road and drive a few miles inland. Welcome to the former Yugoslavia: This is where the first roadblocks went up during the Balkan wars in the early 1990s. Then the ethnic cleansing began. More than 170,000 non-Serb residents fled the fighting or were driven away by Serb militias. Their houses were destroyed in order that the inhabitants would not be able to return. The frontline along the unoccupied part of Croatia was “secured” with more than one million landmines.

But they did not save the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina. In the summer of 1995, Croatian troops overran the area. Tens of thousands of mostly ethnic Serbs fled. Few of them have returned. Most of those who live here today are Croats.

Mile, 46, spent the four years of what he calls Serb occupation on “free Croatian territory.” His house, a three-story building with guest rooms and a balcony for the many truck drivers and tourists who passed through on their way from the coast to Zagreb, Sarajevo or Belgrade, was already in ruins in the fall of 1991.

When Mile returned in 1995, he bought the building next to his destroyed home. He said his former neighbors, who now live in Serbia, don’t want to return. At first, Mile and his family lived in that house. Since then, they have built another impressive house next door. The surrounding villages, however, are still in ruins. A few tourists drive through during the summer – while in winter it is exclusively local residents here with a few truckers arriving for good measure. “I have guest rooms again but there are too few guests,” said Mile. “It’s hardly worth it.”

An oversized border sign marks the crossing into Bosnia-Herzegovina. Then the newly paved road leads past the first mosque to decrepit and war-scarred towns. Many buildings still have bullet holes.

A short way on, a Serb flag welcomes visitors to the Republika Srpska, a reminder that Bosnia remains a divided country. Aside from the Serb “entity,” there’s also the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which consists of 10 separate cantons that are either majority Muslim or majority Croat. On the map it looks like a hopeless jumble. In reality, the multinational Bosnia that existed before the war is now made up of a series of mono-national entities.

Jajce is one of the most astonishing places in the world. A waterfall runs directly through the center of the old town, which is characterized by 500 years of Ottoman rule. Remnants of a medieval city and a Roman fort lie under the town. But the war has left little behind of the Jajce that can still be seen on postcards from the 1980s.

Most of the centuries-old Ottoman houses are dilapidated. Not a single cafe with a view of the waterfall remains. The grill restaurant next to it lies in ruins. Prior to the war, it was always packed. Why is no one trying to stop the decay of this potential goldmine of tourism?

“The international community handed responsibility for reconstruction back to the local administration too soon,” said Zoran, a Bosnian Serb from Jajce who left when war broke out in 1992. “It’s run by the Croat nationalist party, while the Muslims are the opposition. And they are at loggerheads.” Zoran, 50, stands next to his car with a Swedish license plate. He recalls “when Croats and Muslims began to attack the Serbs,” and his flight to safety in Sweden.

Shortly thereafter, Muslims and Croats began to fight each other in Jajce. The remaining civilian population left the city – the majority has still not returned home. Zoran tried in 1998, the year the UN administration proclaimed as the “Year of Returns.” But he soon discovered he was not welcome in postwar Jajce.

The feeling wasn’t confined to Serbs. “Muslims weren’t much better off,” said Zoran.” Construction material and financial assistance either never arrived or it was delayed. The Croatian neighbors fared much better. ”That was part of the strategy of the Croatian nationalist party: They want to prevent other ethnic groups from returning to Jajce. Because if they didn’t, they would no longer be able to automatically win every election.”

Two years later, Zoran went back to Sweden. Since then, he comes back every two or three years during the summer “to look after the house.” He has ruled out returning to Bosnia for good: “What would I do here? This is no longer my country. That country was destroyed.”

Along the road to Sarajevo, a number of new mosques have gone up. “Many of the old houses of worship were destroyed during the war,” said Suljo, 45, a Bosnian Muslim from Sarajevo. “Since then, Saudi Arabia has funded a number of new buildings. But they don’t resemble our Bosnian mosques; instead, they look like McDonalds.”

The facades of Sarajevo’s buildings are crumbling. Trash litters the grounds of the old Ottoman fort above the Bosnian capital. The national library, which was reduced to a charred shell in 1992, is still a construction site. “You could check out books here before democracy was introduced,” Suljo said bitterly. “Look at the building today and you’ll know what democracy is good for.”

Suljo, an electrician, fell severely ill two years ago. He lost his job at the airport, which was well paid by Bosnian standards. Officials finally ruled that he was eligible for worker’s compensation just a month ago. He now receives €60 ($76) a month. “That’s just enough to cover the heating bills during the winter.”

Suljo and his wife Jasna now can no longer afford to send their children to the integrated private school. They now attend a Muslim-Croat school dubbed “Two schools under one roof,” a frequent feature in this part of Bosnia. There the children are taught according to their national heritage.

But in this case it’s hard to say who is which nationality. Suljo is a Muslim, Jasna a Croat. “In the end, the children decided to enroll in the Muslim class,” Jasna said. “Now they learn in history that their mother’s people attacked their father’s people in 1992. In the Croatian class, they would have learned the exact opposite.”

The village of Galici used to consist of 20 houses. Not anymore, says Stejpo, a Croatian Bosnian: “Now there’s just one besides mine. But it’s deserted since the owner moved down into the valley to be with his wife.” What happened in Galici? “We weren’t even 20 years old back then,” he said. “And I was the biggest nationalist of them all.”

The young Croat had never had any interest in his classmates’ nationalities until the war broke out. But then a wave of propaganda hit central Bosnia in 1992. “It didn’t take long before we were convinced that Serbs and Muslims were gunning for our lives,” Stjepo said.

Today, a large cross towers over a hill at the edge of what used to be the town of Galici. A wall runs alongside the cross with the likenesses of 17 men etched into it. They all died between 1993 and 1995. Or rather, in military parlance, they all fell in battle.

Stjepo is not proud of what he did during the Bosnian war. “We were very young back then and incredibly stupid,“ he said. „But we had to defend ourselves. I figured out later that the people on the Serb and Muslim sides were just as stupid. And our politicians exploited all of us.”

Stjepo is sure that the heads of the national parties and militias profited from robbery, trade on the black market, racketeering and extortion. “My generation had to do the dirty work,” he added. “And as a thank you, all we got was a kick in the butt.”

Stjepo says he learned his lesson and wants to pass that on. He bends over his 10-year-old son and tells him: “Just remember one thing. We’re proud to be Croats. But we also know that Bosnians are the best people in the world. Regardless of whether they’re Croats, Serbs or Muslims.”

Deutsch

Deutsch  Naški

Naški  English

English